Symposium Expands Perspectives, Reveals Mystery

by Brian Crawford

The name George Washington was mentioned only one time in a seven hour symposium at Fort Ligonier on the Seven Years’ War. Impressive. In fact, despite Southwestern Pennsylvania itself was little spoken of despite being littered with towns and roads named for people involved in this global conflict, (Braddock, Pittsburgh, Forbes Road, Duquesne, and so on) and despite the fact this global conflict, sparked in Jumonville, Fayette County, had engulfed this entire area. I found this refreshing.

Four presenters took what many of us know of as a regional conflict which we call the “French and Indian War” involving the British and French Empires, as well as several indigenous nations and confederacies, and opened our eyes to a wider world conflict. Ligonier a Western Pennsylvania town, named after French man serving in the British military, seems like an appropriate venue for such an endeavor. In addition to expanding our understanding of the scope of the war, the symposium revealed how the war has a hidden legacy in the beginning of abolitionism still felt today, and the event even ended with a mystery, a mystery 260 some years in the making.

The Seven Years’ War touched every corner of the globe and, in Jamaica, an uprising of enslaved people brought awareness of the suffering slavery manifests to the people of Great Britain. This happed through publications covering what is called Tacky’s Revolt. Dr. Maria Alessandra Bollettino of Framingham State University in Massachusetts, the symposiums second speaker, gave a presentation on the plight of the people enslaved in Jamaica, the brutal conditions they lived in, the history of their voyage from Africa, 37 percent from the Gold Coast (modern Ghana), and experiences of war in Ghana that taught them how to fight in battle. It’s a rebellion little known full of complexities that had enormous implications which we still are feeling today.

One man I spoke to told me he was “jazzed” to hear about Jamaica. He appreciated the detail of which Bollettino laid out the situation which included a more direct involvement of the British government in the Jamaican colony versus the northern colonies. This could be seen through demographics; ninety percent of the Jamaican population was made up of enslaved people. “It was a different type of enslavement that took place in the colonies because there was more direct involvement by the U.K., Jamaica (was) strictly economical, you know, getting sugar and so forth.”*

Dr. Andrew Bamford, the first speaker, joined the symposium from across the pond via a zoom presentation to highlight a failed British attempt to gain a foothold in France showcasing the vast differences in the size of the conflict between war in mainland Europe versus the northern French and British colonies and indigenous nations. His presentation showed how much larger in scale the battles were in Europe which reinforced how much larger this war was globally than many of us often consider.

Conversely, Professor Jim McIntyre of the Seven Years’ War Association and the third speaker, educated on the different partisan, or light infantry, cultures among the different factions of the war both in North America and in Europe including how many similarities stretched across groups who had never even interacted with each other. His presentation sought to show similarities across the different combatants and thus paint the war in a more all encompassing perspective. McIntyre laments how both European and American focused historians often get caught up in a type of tunnel vision that misses the opportunity for a full perspective.

A prime example is the American Revolution. We’re taught about taxation without representation being a catalyst for the rebellion and that’s not untrue but it misses a larger perspective. Understanding a global perspective of the Seven Years’ War brings the taxation issue into context. What’s often missed in our education of the French and Indian War is the greater influence of the larger Seven Years’ War. During the war colonial forces had been sent by Britain to other theaters in the greater war. Now imagine having your child sent to a foreign land and then being told you must now pay a tax to the crown for the privilege. I asked the professor about this.

“I think the other big part to keep in mind is a lot of them don’t come back and it’s like, okay, you want to tax me? And, you know, we won the battle here. So you all send my son to Cartagena and he died. So, yeah, I think there’s a couple of layers to the problems going on here.”**

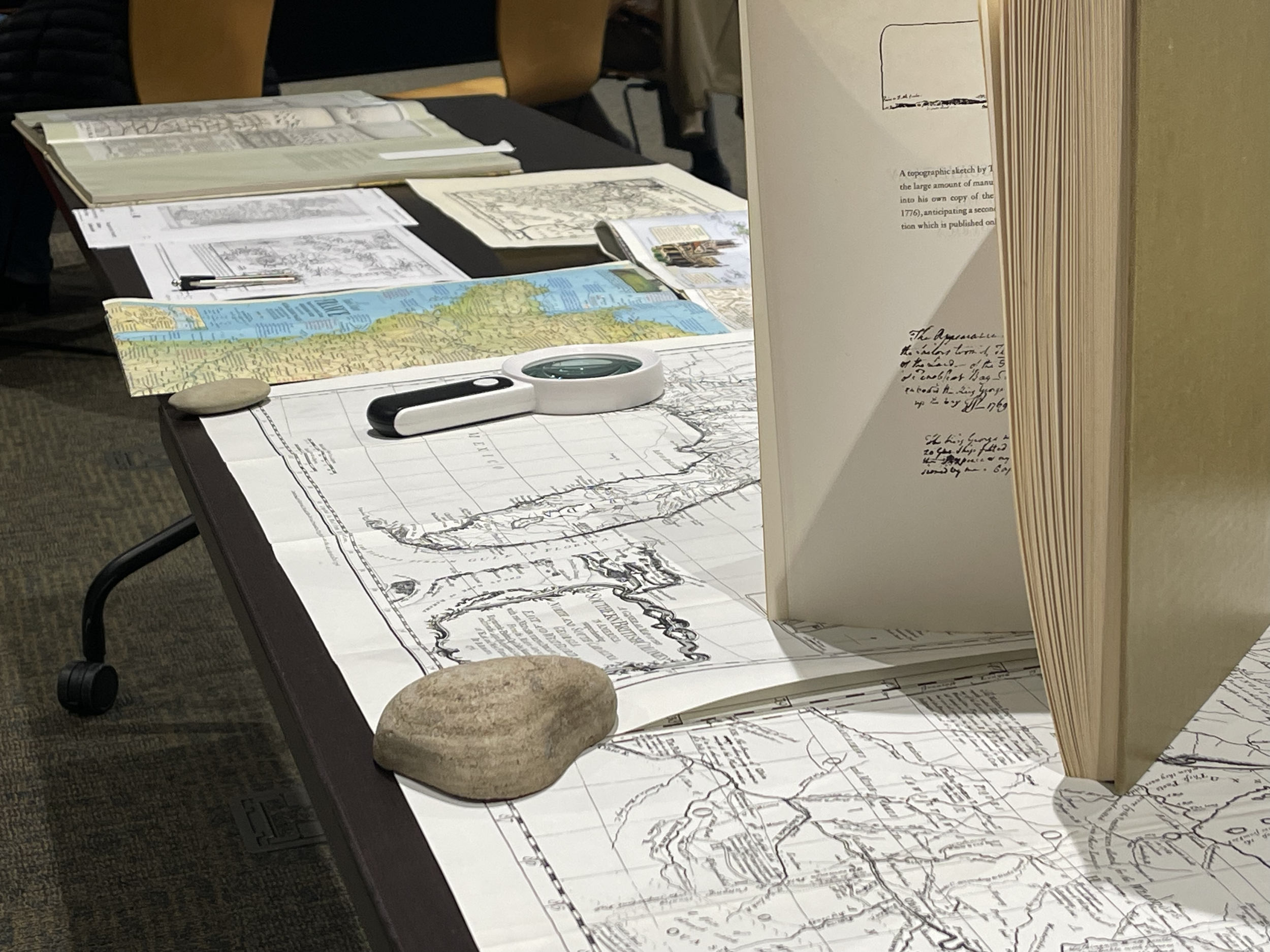

The Symposium ended in mystery. Matt Gault, Fort Ligonier’s Director of Education, the fourth and final speaker, reintroduced the audience to an officer’s uniform the museum had on display for many years. After speaking to a historical tailor the museum staff learned that this uniform was actually a rare touring coat. Additionally the museum acquired a painting and to their surprise the very coat in their possession was featured in this piece of art. In this piece, the coat was being worn by Lord Bruce of Tottenham. Lord Bruce appeared to be a slender man and the coat is a slender fit. Mystery solved. Well, not exactly. Further research has uncovered multiple different paintings featuring the same coat complicating this 260 year old mystery. If you have seen this coat, pictured in this article, reach out to the staff of Fort Ligonier, maybe you can help solve the mystery!

As if the revelation of a 260+ year old mystery wasn’t exciting enough, the attendees were surprised with a rare gift, a trip down to the archival room with collections manager Meghan Budinger to see the coat up close and in person, without glass walls or other barriers. Budinger pointed out alterations made to the coat and other aspects of the coat she and the team at Fort Ligonier need to consider while wearing their sleuth hats and tracking down the coat’s original owner.

At the very beginning of his lecture, Dr. Bamfort expressed the importance of putting your feet down onto the ground where history happened. Fort Ligonier’s Seven Years’ War Symposium merged academic education, presented in a easily digestible way, and provided an opportunity to set foot in a place where soldiers, including the young Colonel George Washington, prepared for their march to Fort Duquesne. I recently explained someone who enthusiastically told me about Aerosmith’s farewell tour coming to Pittsburgh that this symposium is my Aerosmith concert. I wasn’t disappointed.

For the record, this report referred to George Washington twice as many times as the day long Seven Years’ War Symposium.

*The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland came to form through the Acts of Union 1800. The occupying nation would have been the Kingdom of Great Britain which comprised of England, Scotland and Wales.

**Cartagena is a city in modern day Columbia.